“Language is the most powerful tool we have. Let’s use it well.”

Surviving Safeguarding [1]

When I published my first blog back in the summer of 2019, I knew language was important, but so many things I’ve written, spoken about, read and heard since then have convinced me that language matters even more than I thought five years ago.

The words we use are powerful. They paint pictures in our minds. These images, and the ideas they generate and reinforce, influence the way we all think, feel and behave. They reflect, and shape, our view of ourselves, each other and the way we work together. Speak volumes about the past and affect all our futures. But I genuinely believe that because the language of social care is so deeply entrenched, we don’t think enough about the true meaning or impact of the words we use, the story they tell, and the future they shape.

So, here’s a refresh of my original ‘Why language matters’ post – to reiterate what I said then and reassert the importance of paying attention to the words and phrases we all use.

Sticks and stones

“Reading my SW files a few years ago and seeing me described as manipulative by a teacher I’d trusted shattered me. That teacher has since passed (while I was still at the school) and I’d grieved her for years. Was tough to take and people think it’s just words. It’s not. I was 14.”

Careleaver123 [2]

‘Sticks and stones may break my bones, but words can never hurt me’. So the old saying goes. In reality though, the damage done by careless use of language can last much longer than the time it takes a broken bone to heal. Too often our language shows an absence of kindness, and even worse a lack of interest in what really matters, and what will really help.

Wendy Mitchell wrote and spoke many times about the impact of people’s language on her. About how when her doctor delivered her diagnosis of dementia when she was 58 years old, he said “there’s nothing we can do”. How the first question her manager asked when Wendy shared her diagnosis was “how long have you got?” How “if someone tells you day after day that you’re a ‘sufferer’, you end up believing it.” She emphasised how language can make or break someone and suggested that “language is the cheapest thing to change”. [3][4]

The words we use, and the way that we use them, can change lives. For the better, when used with empathy and compassion, but too often for the worse, as we wield words like weapons, and inflict lasting pain.

The very same language we adopt as part of our professional identity and to feel included, so often denies other people their own identity. And our jargon and acronyms so easily exclude. We refer to CHC, CQC, DOLS, ICBs, MCA, MSP, NRPF. We attend DST, MDT, MARAC, MAPPA and VARM meetings. We work with AMHPs, ASYEs, OTs, and PSWs, in teams with acronyms as names.

Our language should heal, not harm.

Build bridges, not walls.

Them and us

“This labelling and classification of people remains a “constant drag that means we never get beyond consideration of ‘them’ and ‘us’.”

Sara Ryan [5]

As well as the direct impact words can have on all of us, language also influences the way we think about, and behave towards, each other. Throughout history, words have been used to deliberately divide and dehumanise. Eugenicists in the late 19th and early 20th Century described disabled people as ‘feeble minded’ and ‘social rubbish,’ while the Nazi regime labelled disabled people as ‘useless eaters’ and ‘lives unworthy of life’ – narratives used to justify horrific atrocities. And more recently, dissent and violence has undoubtedly been fuelled through the calculated framing of migrants. ‘Illegal’. ‘Marauders’. “An invasion on our southern coast”.

When we pay attention to the terms we use to communicate about people in social work and social care, we expose so much about the attitudes and assumptions that shape our practice.

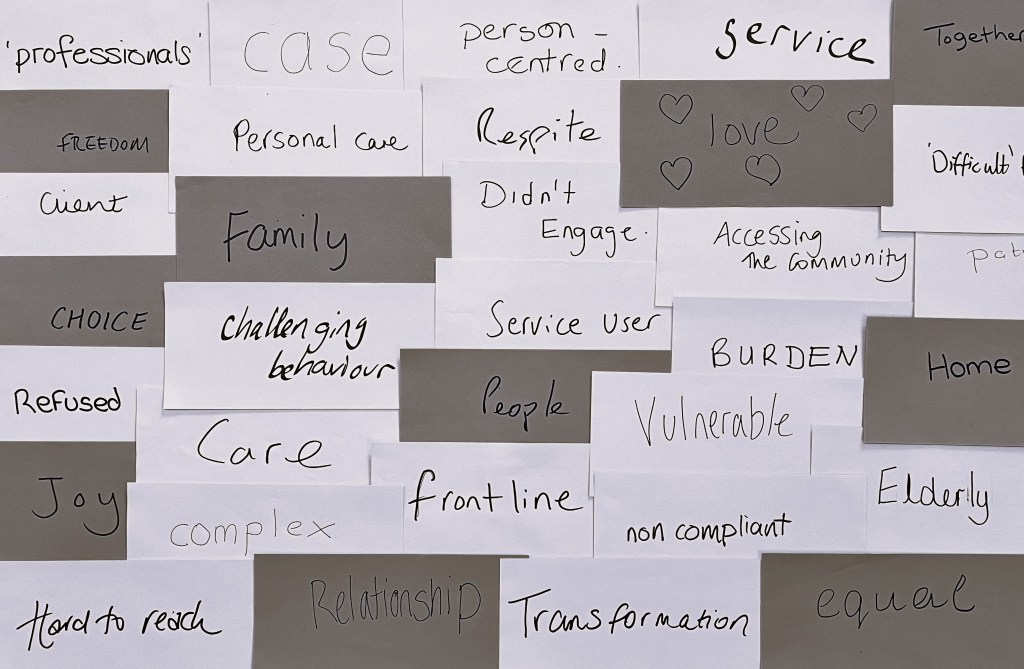

We don’t talk much about people. Instead, we talk of ‘customers’, ‘service users’, ‘clients’, ‘patients’.

‘Those’.

Often, we don’t even identify people as human beings at all. They are ‘cases’. ‘Referrals’. Reference numbers from our ‘case management’ systems.

Terms like ‘deficient’ ‘deviant’ ‘disorder’ ‘divergent’ imply that some people are different to what is expected. To what is ‘normal’. Overlook how we are all different. Ignore how alike we all are.

Terms like ‘vulnerable’ frame people as weak and needy, while references to ‘demand’, ‘burden’ and ‘respite’ imply people are an inconvenience. Getting in the way.

And we use strange jargon to talk about where these ‘other’ people live, their friends and family, what ‘they’ do.

This different, distant group don’t move house or live in homes like we do. They are ‘placed in’ ‘settings’. ‘Schemes.’ ‘Accommodation.’ ‘Units.’ ‘Beds.’

They don’t have a wash, brush their teeth, and get dressed like us. They have ‘personal care’. They are ‘fed’ and ‘toileted’.

We have family and friends, lovers, soulmates. They have ‘carers’, ‘peers’, ‘nearest relatives’, ‘next of kin’.

We go to work, meet friends, exercise, go shopping. They ‘access employment’, ‘maintain relationships’, ‘access the community’, and ‘engage in meaningful activities’.

We fall over. They ‘have a fall’.

We get cross, angry, upset. They ‘display challenging behaviour’.

We have vague plans, and things we might get round to doing one day. They have ‘outcomes’ to achieve.

We wouldn’t use this language in our kitchen with our family, or at the café or pub with our mates. [6] If social care is all about people living gloriously ordinary lives, why do we use language that suggests little is ordinary, never mind glorious?

This language influences our perception of people and exposes the assumptions that drive our practice.

We frame people as passive recipients of ‘care’. ‘Service users’. ‘The cared for’. ‘Those with care and support needs’. There’s no sense of reciprocity in this narrative. Of people’s gifts and potential. The need to be needed. The right to choice and control. As such, people are seen, treated, and expected to behave as ‘people who need help’, not active citizens with experience, skills, ideas and knowledge to contribute. With rights to be upheld.

As well as implying superiority, our language suggests ownership.

‘Our customers’. ‘My cases’.

All this framing helps to define our roles and justify our paternalistic approach.

‘Professional’. ‘Assessor’. ‘Care manager’. ‘Case co-ordinator’. ‘Carer’.

‘Looking after’. ‘Protecting’. ‘Caring for’.

‘Keeping people safe’.

In addition to labelling people, we label how people behave – particularly when people don’t act how we believe they should. We use phrases like ‘difficult’, ‘challenging’, ‘refuses to engage’, ‘non-compliant’, ‘hard to reach’ all too readily. This language implies the person is the problem. It overlooks what’s happened to them, what’s happening around them. What they are communicating, and why. It justifies the use of medication, restrictions, restraint. And it blames people instead of acknowledging our own influence and impact. Our failure to listen to what really matters to people. To fully involve people in conversations and decisions about their lives. To use language people understand.

Our failure to understand people.

Maybe it’s us who are refusing to engage? Maybe it’s our behaviour that challenges? Maybe we’re the ones who are the hardest to reach? Maybe that’s deliberate?

We refer to ‘the frontline’. ‘Duty’. ‘Officers’. The language of battles. Us v them. Words that imply we’re on opposing sides. Often it feels like we are.

All these words and phrases erase personhood and identity. Create distance. Imply difference. Not like ‘us’. Not so important. Not so human. Not so visible.

And once you’re not so visible, your life becomes that bit less valued. And once you’re seen as less valuable, you become a whole lot more vulnerable.

Once you’re written out of the story, you’re effectively written off.

“People were ‘patients’ or sometimes ‘service users.’ This language protected me from the reality of what I was doing to people caught in the system… I learnt that dehumanising people through my use of the language of the professional made it easier for me to cope.”

Elaine James, Rob Mitchell and Hannah Morgan [7]

Easier to cope.

Easier to ignore.

The social care sorting office

When we pay attention to language, we notice what it exposes. If we look at the words we use about our practice, they reveal the way our system is set up to continuously move people around.

Our sorting office approach.

Despite endless references to how ‘person-centred’ we are, our language reveals how processes are at the centre of our practice, not people.

‘Cases’ ‘transition’ to adult social care from children’s services. We ‘screen’, ‘triage’, ‘signpost’, ‘allocate’ and ‘refer’. We ‘discharge to assess’. We determine ‘pathways’ and ‘journeys’, which often result in a ‘placement’ or a ‘transfer of care’.

We’ve industrialised ‘care’ and automated our processes, labelling and processing people like parcels in a sorting office. And as such, we’ve removed all traces of humanity to such an extent that we think it’s ok to refer to people as numbers and cases. Indeed, our sorting office approach relies on us maintaining distance. Real lives are complicated and messy – tangled webs of aspirations, expectations, memories, dreams, hopes, fears, opportunities, barriers. Real lives don’t fit into our neat categories – especially not good lives. If we focus only on problems and attach the corresponding labels, it’s so much easier to fit people into the boxes on our forms, channel them down our one-size fits all, linear conveyor belts and apply our standard service solutions.

It’s much quicker to apply quick-fix solutions than to really explore what a good life looks like to someone and how we can work with them to achieve it. ‘Personal care needs’ are quickly met with the purchase of a standard ‘four calls a day’, but you can’t buy friendships, hobbies, jobs, love. All those things that enhance our lives rather than just maintain our existence – all those things that make us unique, make us who we are – don’t come in off-the-shelf packages. But if we don’t recognise people as unique human beings we don’t need to think about their lives as a whole. And if we dehumanise them enough – if we forget they are mums, dads, daughters, sons, sisters, brothers, friends, us – we don’t even feel uncomfortable imposing solutions we’d never want for our own family or friends.

For ourselves.

Smoke and mirrors

“I’ve been constantly fascinated by the ability of social care to reinvent it’s language but never its values”.

Mark Neary [8]

Language evolves. The Oxford English Dictionary publishes four updates a year, with new words and phrases added and definitions revised. The language of social care evolves too. We talk of personalisation and co-production, strengths-based approaches, and asset-based community development. But all too often, while we’ve introduced different terminology, we haven’t changed our behaviours or our bureaucracies at all.

A new vocabulary imposed from above without an associated shift in power and practice can be misinterpreted internally and greeted with suspicion externally – particularly if the new language is seen as a thinly-veiled attempt to divert people from our doors and relinquish our responsibilities. And indeed, many of our ‘buzz words’ are code for exactly that.

‘Prevention’. ‘Independent’. ‘Community’.

Missing words

The language we use in and about social care matters.

The words we don’t use enough matter too.

Love. Home. Belonging. Joy. Hope. Rights. Trust. Sorry.

People.

We.

Us.

The absence of these words in relation to people’s lives and our practice reveals just as much as the words that dominate.

We can continue to produce glossaries, jargon busters, factsheets, and guides to demystify our jargon and translate our processes into ‘plain language’. We can employ ‘navigators’ and advocates to help people understand the complexities of social care and negotiate their way through. But in doing so, we’re just perpetuating the system.

We can make some simple switches to the way we talk. Replace ‘those’ with ‘people’. Refer to ‘working with people’, not ‘dealing with cases’. Say ‘support’ instead of ‘care’ or ‘services’. Use ‘chose not to’ instead of ‘refused’. Ask ‘why?’ instead of using words that blame.

Little changes can make a big difference. These subtle shifts in language can help us refocus and rehumanise our practice.

But.

We’ll have to keep referring to people as numbers, referrals, beds, ‘mum’ if we keep forgetting to ask their names. If we continue to pass people round like parcels, we might as well call them cases. We can’t talk of connection when we’re still signposting people away. We can’t focus on what matters and what’s strong, when we start with ‘what’s the matter?’ and ‘what’s wrong?’. We can’t refer to people’s homes if where they live feels like a ‘setting’ or a ‘placement’, not somewhere they belong.

Language matters, and I think words are just as important as actions, but we also need action – not just alternative words.

We need to dismantle our social care sorting office with its associated barriers, assumptions, battlegrounds and quick fix solutions, and return our focus to people, not processes. Lives, not services. Us, not them and us.

We need to stop assuming the role of the expert in people’s lives, and reclaim our role as experts in listening, making connections, upholding human rights, and building lasting relationships.

We need to welcome people rather than pushing them away, trust our instincts, our judgement, and the people we’re working with. Make decisions with people, not for them, and focus on capabilities and possibilities rather than problems and risks.

We need to change our practice as well as our language.

We need to rewrite social care.

References

[1] Divisive, demeaning and devoid of feeling: how social work jargon causes problems for families, Surviving Safeguarding, Community Care, 10 May 2018

[2] Reading through my SW files a few years ago… Careleaver123, Twitter, 23 April 2022

[3] Somebody I used to know, Wendy Mitchell, Bloomsbury, 2018

[4] Which me am I today? Wendy Mitchell

[5] Love, learning disabilities and pockets of brilliance, Sara Ryan, Jessica Kingsley Publishers, 2021

[6] The five tests. Tricia Nicoll, Gloriously Ordinary Lives

[7] Social work, cats and rocket science, Elaine James, Rob Mitchell and Hannah Morgan, Jessica Kingsley Publishers, 2019

[8] The words on the tin Mark Neary, 2 December 2018

Leave a comment