“A person-centred approach puts people at the heart of care.”

“The person-centred approach treats each person as an individual human being”

“A person-centred approach considers the whole person.”

If you knew nothing about social care, I imagine you’d assume and expect that people and what matters most to us are at its beating heart. Indeed, it’s what care and support is all about. “The core purpose of adult care and support is to help people to achieve the outcomes that matter to them in their life.” [1]

Perhaps you’d think it was odd that so many organisations feel the need to state that ‘we are person-centred’ (increasingly alongside references to being strengths-based rights-based recovery-orientated trauma-informed anti-racist outcome-focused asset-based community-focused – we do love a hyphenated approach don’t we!?)

What else would they be?

However, those of us with experience of either working in, or seeking or drawing on support from, social care – or both – know that too often processes and paperwork and performance metrics remain at the centre, and somehow in this labyrinthine world we’ve forgotten that our purpose is people.

We’ve forgotten that we are all human beings.

We’ve forgotten to be human.

The roots of ‘person-centred’ thinking and practice lie in humanity and identity and possibility. In who people are, were, want to become. In what people have, would like, can give. In curiosity and connection and choice and control and creativity and contribution.

But often, while organisations may claim to be ‘person-centred’ to “[certify themselves] as morally pure and appropriately avant-garde [behind] the curtain… business [is] proceeding as usual: preserving one’s turf, creating dependencies, and protecting a livelihood earned by catering to people’s needs, deficiencies and problems.” [2]

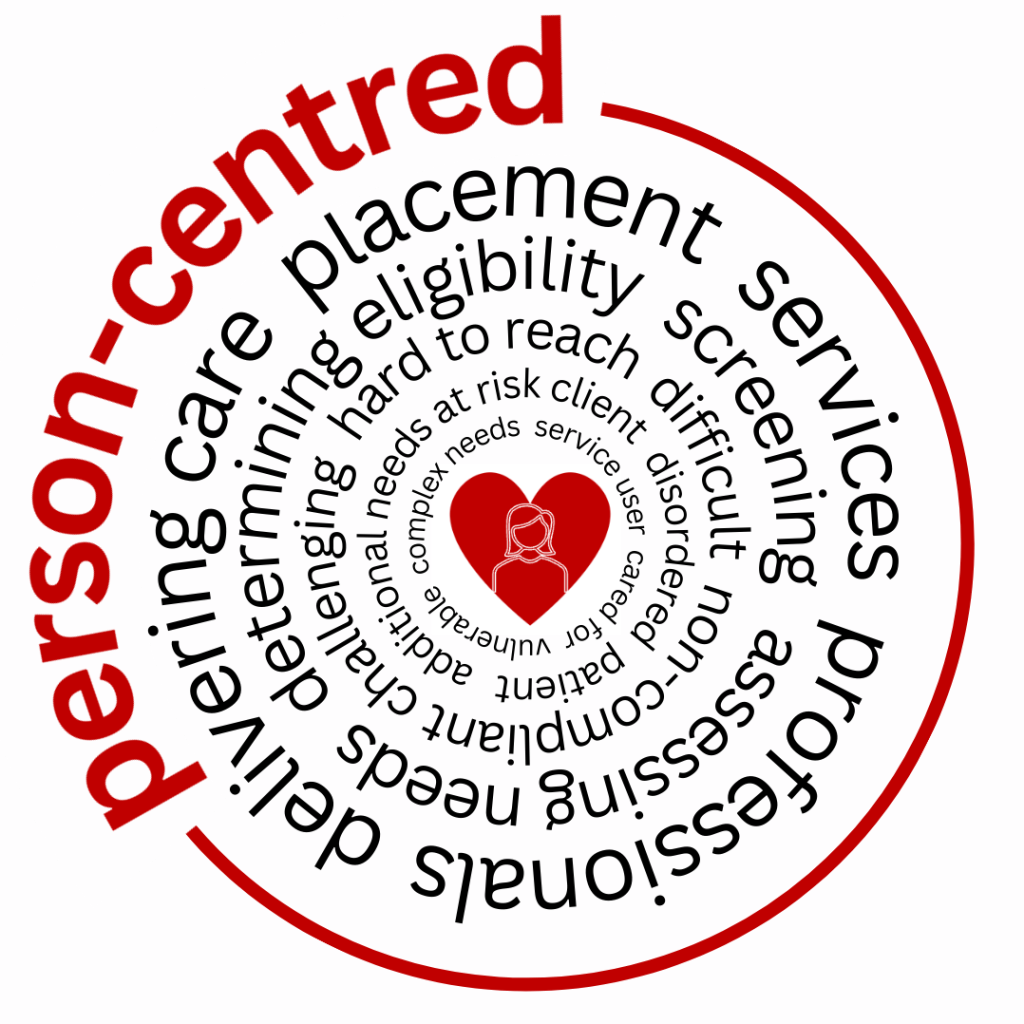

We’re very good at saying we’re person-centred, but when we pay attention to what else we say, our language reveals we’re maybe not so good at being person-centred.

Person

“The service aims to provide a person-centred and holistic approach… We encourage the PWS to achieve their maximum potential so that they may live as independent a life as possible.”

“We are person-centred in how we support a service user to ensure we meet their individual needs.”

Oh, the irony. We’ve bolted the term ‘person-centred’ on to a system that doesn’t recognise or value people as people! A quick Google search reveals organisational web pages that clearly state “we take a person-centred approach” and in the same sentence paragraph page refer to “the service user”, “our patients”, “those with Autism”, “our clients”, “those with complex and profound social, emotional and behavioural needs”, “our residents”, “those in our care”, “the People We Support (PWS)”, “the PWS”. Several such pages also feature one or more of those ubiquitous, dehumanising images of bodies without heads.

How can we be person-centred if we don’t register or remember that we’re working alongside actual people!?

Centred

Centred means ‘placed or situated in the centre’. [3]

Our language exposes how rarely people are at the centre of our thinking and our practice. We refer to people as ‘demand’, ‘bed-blockers’, ‘high-intensity users’, ‘inappropriate referrals’. How inconvenient that you require assistance. Don’t you realise you’re disrupting the ‘flow’?

Indeed, if you don’t slot neatly into the centre of our boxes pathways services expectations, we label you as ‘complex’ or ‘challenging’ or ‘difficult’ or ‘non-complaint’.

We blame you for not fitting in.

Centred also means “mentally and emotionally confident, focused, and well-balanced”. “If you feel centred, you feel calm, confident, and in control of your emotions.” [4] I wonder how many people who either work in, or are seeking or drawing on support from, ‘person-centred’ services, feel centred when so much is so fragile fractious fractured.

Person-centred assessment

“Considering the person’s views and wishes is critical to a person-centred system.”

– Department of Health and Social Care [5]

The Care Act 2014 statutory guidance states that “the [assessment] process must be person-centred throughout, involving the person and supporting them to have choice and control.”

There’s not much that could be called person-centred about the assessment process we have created (and when I say ‘process’ I mainly mean form). Indeed, a ‘person-centred assessment’ is surely an oxymoron!?

Over the years I’ve had numerous discussions with social workers about the shift from assessments led by paperwork to conversations led by people and families. The shift from asking ‘what’s the matter with you?’ to understanding ‘what matters to you?’. I’ve written before about one of the concerns expressed in response – ‘What if they ask for something I can’t deliver?’ – and how “this exposes our expectation that ‘the system’ has the solutions, and that services are the solution”. [6]

Another concern I’ve heard on several occasions is, ‘how can we understand what matters most to someone if they can’t communicate?’ Woah. So much to unpick here. The perception that someone ‘can’t communicate’ (see also ‘has difficulty communicating’, ‘has communication problems’, ‘struggles to communicate’…) exposes an ableist and dangerous view of communication, where barriers aren’t acknowledged, needs remain unmet and behaviour is labelled not understood. And the fact that this concern is only articulated when contemplating a shift towards a more conversational, curious, ‘human’ approach also exposes how often ‘traditional’ assessments must – despite what the Care Act 2014 statutory guidance says – disregard “the individual’s views, wishes, feelings and beliefs”. Must overlook “the importance of beginning with the assumption that the individual is best-placed to judge the individual’s wellbeing”, that “the local authority should assume that the person themselves knows best their own outcomes, goals and wellbeing” and that “local authorities should not make assumptions as to what matters most to the person”. Must ignore the fact that “this is especially important where a person has expressed views in the past, but no longer has capacity to make decisions themselves.” Must forget about “the importance of the individual participating as fully as possible in decisions about them.” [7]

So much for nothing about us without us.

Person-centred planning

“Ultimately, the guiding principle in the development of the plan is that this process should be person-centred and person-led…”

– Department of Health and Social Care [8]

The Care Act Statutory Guidance devotes a whole section to ‘person-centred care and support planning’, emphasising that “The person must be genuinely involved and influential throughout the planning process…” [9]

The concept of ‘involving’ someone in their own plan is jarring. If a couple were planning their wedding, a wedding planner wouldn’t refer to them being involved in the plans for the big day. A travel agent wouldn’t refer to involving a family in their holiday plans. A midwife wouldn’t describe someone who was pregnant as being involved in planning their birth. In all those circumstances, the person or people make – and own – the plans, and they decide who else they want to involve.

And yet in the world of social care, we explicitly state that person-centred planning is “where individual people take part in decisions about their health and care.” That “it is essential that the person requiring care is involved in the decision-making process.”

You’re part of (maybe). You’re involved (possibly). But you’re not leading.

You’re not in control.

Because at the end of the day, we’re the professionals. That’s our job. We’re in charge. We know best. And anyway, you’re vulnerable. You’re struggling. You have complex needs. We don’t want to burden poor old you or your beleaguered carers. It’s just easier and quicker if we write up our plan for you and tell you what it says.

We’ll probably maybe possibly send you a copy, so you know what to expect.

“The plan will be both person-centred and person-led, and the Council will take all reasonable steps to involve and agree the plan with the person the plan is intended for.”

“We will create your care and support plan based on your individual needs.”

“We make sure people are on board with the plan for them.”

We may talk about person-centred planning, but we’re still ‘managing expectations’, lowering expectations, and writing off dreams and ambitions as ‘unrealistic expectations’.

“Person Centred Plan: A chance to exercise our power by saying “No” to everything you want to do with your life.”

– Mark Neary [10]

John O’Brien observed how “words like person-centred planning have life in some contexts and in some contexts, they’re just filling out a form”. [11]

Too often plans are just a form process workflow to complete, involving ‘service types’ and ‘care tasks’ and ‘delivery schedules’ and ‘required units’ and ‘unit costs’ and ‘purchase service requests’, where the ‘plan co-ordinator’ is the worker ticking the boxes and choosing from the drop-down lists.

Where the worker selects the ‘main beneficiary’ as either ‘me as a service user’, ‘me as a carer’ or ‘my carer’.

Person-centred care

“Person-centred care is about placing the person being cared for at the heart of care.”

“It involves the service user being placed at the centre of their own care.”

“We deliver person-centred care to elderly clients.”

“We provide person-centred care to those most in need.”

“I ensure the P.W.S. are receiving person-centred care.”

The person being cared for. The service user. Elderly clients. Those in need. The P.W.S.

Passive recipients.

The needy.

Those.

There’s no sense in this narrative of people being valued. Contributing. Having agency. Being in control.

Indeed, there is little sense of people being people at all.

And we’re still trapped in this perception – and reality – of care being something we deliver, like pizza.

A transaction, not a relationship.

Packages of care.

In my previous post I quoted John O’Brien, who wrote about words becoming abstract, floating away as intention and mindfulness is lost from what we’re doing.

We’re very good at saying we’re person-centred. So good, in fact, that the phrase is everywhere. It’s become ubiquitous. But it has also become untethered, detached from the principles and values and ideas and rights and humanity at its roots.

As such I think we have no right to use the phrase until we genuinely see every person as a fellow human-being with gifts, desires and potential, not as a problem to be fixed, and until we see care as a relationship, not something we deliver.

Then, when that belief genuinely underpins how we feel and act, we won’t need to say we’re ‘person-centred’ at all, because it will be obvious.

And because we wouldn’t, and couldn’t, and shouldn’t, be anything else.

References

[1] Care and support statutory guidance, Department of Health and Social Care, GOV.UK, Updated 22 July 2025

[2] No more throw-away people: the co-production imperative, Edgar Cahn, Essential Books, 2000

[3] Centred, Oxford Languages

[4] Centred, Collins Dictionary

[5] Care and support statutory guidance, Department of Health and Social Care, GOV.UK, Updated 22 July 2025

[6] How to be human, Bryony Shannon, Rewriting social care, 10 February 2024

[7] Care and support statutory guidance, Department of Health and Social Care, GOV.UK, Updated 22 July 2025

[8] Care and support statutory guidance, Department of Health and Social Care, GOV.UK, Updated 22 July 2025

[9] Care and support statutory guidance, Department of Health and Social Care, GOV.UK, Updated 22 July 2025

[10] Parley Vouz Health & Social Care? (An A to Z of Carespeak), Mark Neary, Love, Belief and Balls

[11] Personhood and Members of Each Other, Neighbours International, YouTube, 2024

Leave a comment