Last Monday me and Tricia Nicoll chatted for an hour with a group of people who had signed up to our online ‘Gloriously Ordinary Language: Keeping our language human, inclusive and real’ session about ‘carers’.

We opened the session by suggesting that the term ‘carer’ is like marmite – people either love it or hate it. (We did also check how people felt about marmite with a quick poll – and were amused to see an exact 50:50 split. Half the people in the virtual room said they loved marmite, and half said they hated it!)

‘Carer’ is one of those words that really does make me go hmmm. It’s a confused, confusing, contradictory, and contentious term that simultaneously offers and erodes identity, and both affirms and devalues caring relationships.

Are you a carer?

‘Are you a carer?’ is a phrase used ubiquitously on websites and other public information, because the term ‘carer’ is such a slippery one. There’s usually a need to define what the label doesn’t mean along with what it does.

According to the Care Act 2014, ““carer” means an adult who provides or intends to provide care for another adult (an “adult needing care”); but… an adult is not to be regarded as a carer if the adult provides or intends to provide care (a) under or by virtue of a contract, or (b) as voluntary work. But in a case where the local authority considers that the relationship between the adult needing care and the adult providing or intending to provide care is such that it would be appropriate for the latter to be regarded as a carer, that adult is to be regarded as such.” [1]

Clear?

The Care Act statutory guidance defines a carer more succinctly as “somebody who provides support or who looks after a family member, partner or friend who needs help because of their age, physical or mental illness, or disability. This would not usually include someone paid or employed to carry out that role, or someone who is a volunteer.” [2]

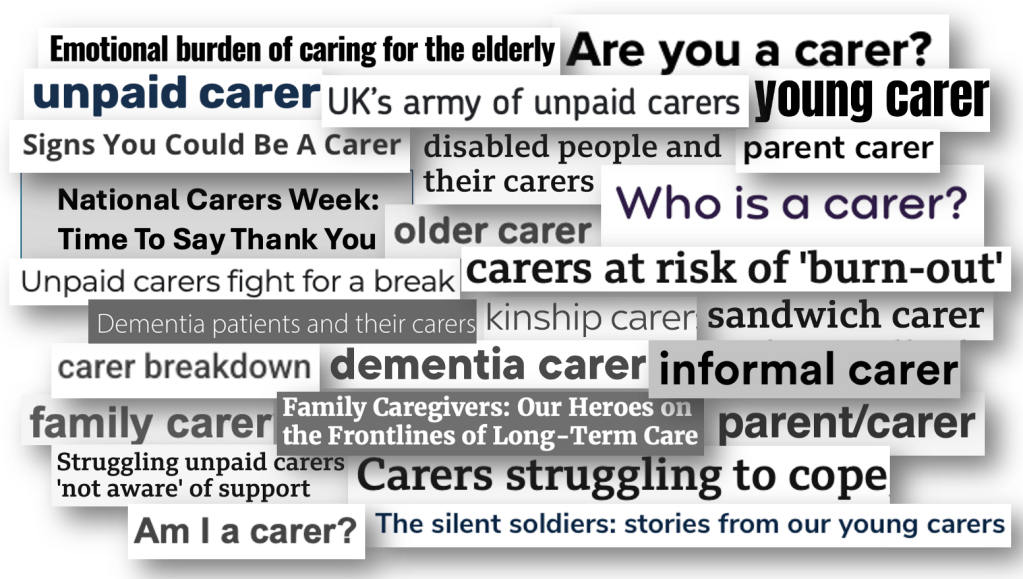

In attempts to add clarity, we add more words, including ‘informal’, ‘unpaid’, ‘family’, ‘parent’, ‘young’, ‘older’, ‘kinship’, ‘sandwich’, ‘dementia’…

Many of these are tricky too.

‘Informal carer’ implies that care is casual, optional, and second rate in comparison to ‘formal’, ‘official’ care, devaluing and demoting caring relationships in favour of ‘care’ as a paid for service/transaction.

‘Unpaid carer’ aims to highlight this role is different to a paid care worker but can cause confusion when people are receiving Carer’s Allowance and class that as payment.

‘Family carer’ suggests a familial relationship, excluding friends and neighbours.

‘Parent carer’ generally requires further qualifiers in relation to ‘parental responsibility’, and the age of the ‘child’ (with various definitions including ‘a child or young person under 18’, ‘a young person aged 18 or under’, ‘a child aged up to 25 years’, and ‘grown up children’) and is further confused by the use of ‘parent/carer’.

And ‘young carer’ normalises the fact that children ‘as young as five’ are being forced to compensate for a lack of adequate resources and support to enable parents to parent, and children to have a childhood.

Regardless of the multiple definitions, people have their own interpretation, often not identifying with the label at all, and preferring to describe themselves in terms of their relationship (daughter, dad, brother, partner, friend…) instead. This may be for a whole host of entirely personal and justifiable reasons, including that people see caring as a natural part of their relationship, or they reject the ‘carer’ identity through reluctance, resentment or because they feel the label is more associated with tasks (‘care duties’) and replaces their relational identity.

“I do not like it and never have. I was a young ‘carer’ and hated being labelled with that.”

– Comment from Monday’s session

Often people want and need their daughter, dad, brother, partner, friend to retain that relational identity too. “We heard from people who draw on care and support that they wanted, for example, their loved one to remain their husband or mother rather [than] become their carer”. [3] People often don’t want to be ‘cared for’ – even when they’re obviously cared about.

“It could make both people boxed into roles they did not choose.”

– Comment from Monday’s session

Carers and ‘the cared for’

In contrast to the identity (welcomed or not) offered by the ‘carer’ label, its application often leads to the removal of the identity of the “family member, partner or friend who needs help”. They become ‘the cared for person’, defined in terms of their relationship to someone else rather than as a person in their own right, with their own rights – or often just ‘the cared for’.

“If you require a joint assessment with your cared for our social care teams will be happy to support this.”

‘The cared for’ are not recognised as individual human beings, and the ‘…and their carer’ phrase is invariably attached, ascribing and affirming subordinate and superior roles.

- “Our service users and their carers”

- “Older people and their carers”

- “Disabled people and their carers”

- “People with lived experience and their carers.” (Argh!!)

While the ‘carer’ has an active role – ‘providing support’, ‘looking after’, ‘giving help’ – ‘the cared for’ person is just that – cared for. A passive recipient. “Someone who can’t carry out everyday tasks by themselves.” “A vulnerable neighbour or relative.”

‘Care’ as a one-way street.

There’s no sense of people caring for and about each other. No recognition of reciprocity, of mutual support. No appreciation that ‘carers’ may also be ‘cared for’. You tick one box or the other.

Someone who depends on you

The ‘carer’ narrative implies a dependent relationship.

‘Do you look after someone who depends on you because of an illness or disability?’

Simon Brisenden suggests that this enforced dependency on a relative or partner is “the most exploitative of all forms of so-called care in our society today for it exploits both the carer and the person receiving care. It ruins relationships between people and results in thwarted life opportunities on both sides of the caring equation”. [4]

As well as the impact on relationships, the notion of ‘carers’ doesn’t sit comfortably alongside the notion of self-directed support. Frances Hasler writes how in the 1980s, as members of the disabled people’s movement were campaigning for the right to independent living, the concept of rights for carers was also growing. She notes how “the carers’ movement, representing female family carers, was based on the construction of disabled people as ‘dependent’”, and how it cast disabled people as “a ‘burden’ shouldered by female caregivers” and excluded their voices from the debate. [5]

The burden of caring

There are numerous references to ‘the burden of caring’.

“Although we know a rise in the number of people requiring care is a burden on both genders, it is weighing on the shoulders of women more frequently.”

“Unpaid carers are suffering under the burden of looking after loved ones.”

I’m in no way trying to detract from all the work that caring involves, or gloss over the huge issues of gender inequality highlighted here, but this narrative labels and blames the person being ‘cared for’ as a burden.

“It can also create guilt or pressure for the person being cared for, i.e. they feel a burden.”

– Comment from Monday’s session

And surely by now we all know that the dictionary definition of ‘respite’ is “a short period of rest or relief from something difficult or unpleasant”? [6] Yet still we stubbornly continue to use this term.

Struggling to cope, breaking down, burning out

The blaming narrative extends to carers too.

We label family members who have a right to be recognised, heard, understood, supported and included as ‘difficult’, ‘challenging’, ‘demanding’, ‘hostile’, ‘interfering’.

And we blame carers for “finding it difficult to balance the needs of loved ones with their own wellbeing”, “struggling to hold down jobs”, “not realising they have rights”, “not understanding what help is available”, “not recognising themselves as carers”.

Despite our duty to determine “not only the carer’s needs for support, but also the sustainability of the caring role itself”, [7] when someone is no longer able or willing to continue in their caring role, we’re quick to suggest they’re ‘struggling to cope’ and ‘breaking down’ and ‘burning out.’

“I hate the term carer… the term makes everything feel like it sits with me. If I say l don’t want to be her carer – does this mean I do not care?”

– Comment from Monday’s session

So much pressure. So much guilt.

We happily promote self-care peer support advocacy mental health support respite services to ‘prevent carer breakdown’, while blithely failing to acknowledge the role of public services in inducing anxiety and frustration and despair with our endless bureaucracy and our continued failure to listen and to be useful and to get out of the way.

Britain’s army of unpaid carers

The language of war we’re so fond of adopting is rife in relation to carers. Armies. Battles. The frontline. Duty. Soldiers. Heroes. Sacrifice.

In addition to the ubiquitous ‘army of carers’ metaphor, the ‘hero’ label is also pervasive. “Unpaid carers are society’s heroes”. “Young carers are heroes with capes that can’t be seen”.

This notion of carers as ‘heroes’ is problematic in multiple ways. The term implies carers are strong, powerful protectors of the weak and helpless. Super-human, in contrast to the not quite human ‘cared for’. The saviours and the saved.

Describing carers as heroes suggests they are extraordinary, ‘soldiering on’ against the odds. This narrative attaches extremely high expectations, implying failure if someone is not willing or able to continue caring, and diluting the case for desperately needed practical, financial, and emotional support.

The suggestion that caring is a ‘duty’ places ‘caring responsibilities’ firmly with families rather than with wider society or the state.

The narrative of ‘sacrifice’ further degrades people drawing on support by implying carers are doing a job that nobody else would want, and that it’s by choice. The term also draws attention to what is lost, rather than what is gained. And, like the hero narrative, it suggests caring is a natural element of relationships, again deflecting attention from the need for other options.

Inevitably, the suggestion of invisibility runs alongside the military metaphors, with endless references to carers as “unsung heroes”, “a hidden army” and “the forgotten frontline”.

“Please stop referring to us as hidden carers. We are seen and heard every day. We’re not hidden, just conveniently ignored – and therein lies the problem.”

– Mina Akhtar [8]

Therein lies a problem, but the main problem is that while campaigns focus on “making carers more visible”, the people drawing on their support are overwhelmingly absent from this narrative altogether.

A huge amount of gratitude

“We all owe unpaid carers a huge amount of gratitude for the time and care they give their friends and family.”

“We want to say a big thank you to all our unpaid carers. Please continue to do the work you do.”

Platitudes abound, particularly during ‘Carers Week’ – the annual “awareness campaign that provides a unique opportunity to honour and appreciate the efforts of millions of unpaid carers in the UK”, and “gives us a chance to recognise the amazing contributions these unsung heroes make to people’s lives”.

Thank you. It’s important you get the recognition you deserve. Please continue to do the work you do. We’ll thank you again next year. You’re on your own until then.

These warm words are often linked to the acknowledgement that carers are “propping up the system”, and that “without the help provided by millions of unpaid carers across the UK our health and social care system would collapse.”

“Unpaid carers are the unrecognised heroes who save the NHS and social care from being overwhelmed every day.”

Unpaid carers are sustaining the system.

Isn’t that the wrong way round?

“Make me one more cupcake for being a carer in carers week and I’ll throw it at you! 🧁”

– Comment from Monday’s session

Economic value

Unpaid carers “contribute care equivalent to 4 million paid care workers to the social care system adding £162 billion per year to the economy in England and Wales, the equivalent to a second NHS.”

‘Unpaid care’ is “valued at £445 million per day”. “Unpaid carers save the government £162bn per year.” “Within a decade, the economic value to the country of unpaid carers has increased by 29% – a hefty saving to the health care budget.”

These huge sums increase year on year, but it’s hard to see the benefit of this narrative. Highlighting how carers “save the taxpayer millions of pounds” means any alternative is unlikely to be either vote or investment winning. And focusing on ‘savings’ overlooks the massive financial, physical, and emotional cost to people and to relationships.

Economically devalued

As well as the narrative of the economic value of carers, there’s a contradictory counter narrative that presents carers as “economically inactive”.

“The cost to the economy of unpaid carers’ withdrawal from the labour market is estimated at around £1.3bn annually, whilst the potential gain of enabling them to work has been calculated as £5.3bn per year.”

There are numerous references to carers ‘giving up work to care’, and repeated calls to ‘help unpaid carers back into work.’

This highlights one of the fundamental issues we face. We recognise ‘work’ in terms of earning money, value people in terms of their economic contribution, and attach and affirm identities through paid roles. Therefore, by definition ‘unpaid care’ is not ‘work’. But someone who is paid to ‘care’ is working (and is as such not a ‘carer’). So, what’s the difference?

One is a relationship, and not valued (‘informal’, ‘unpaid’ caring).

One is a transaction, and valued (‘formal’, ‘paid’ care) – though arguably also nowhere near highly enough.

“As a south Asian the name carer is a new word in my family/ community so not entirely certain where I stand with this term at present.”

– Comment from Monday’s session

It’s only when we step into serviceland that the ‘carer’ label is demanded and attached. Indeed, Madeleine Bunting describes it, as “a reductionist description of a relationship developed to suit the bureaucratic need”. [9]

So maybe it’s time to change the conversation?

Time to stop dividing human beings into ‘carer’ and ‘cared for’, active and passive, provider and consumer. Time to remember that everyone has something to offer and that we need each other. Time to recognise that caring is work, and that “if we need it, we must compensate it.” [10] And time to invest in people and places, to make sure that everyone’s human rights in relation to autonomy, dignity and family life are recognised and upheld, and that we all have the connections, relationships, resources and support in place to live genuinely full and flourishing lives.

The lives we choose to lead.

References

[1] Care Act 2014, c.23, 2014

[2] Care and support statutory guidance, Department of Health and Social Care, GOV.UK, Updated 22 July 2025

[3] Care and Support Reimagined: a National Care Covenant For England, Archbishops’ Commission on Reimaging Care, January 2023

[4] Independent lives? Community care and disabled people, Jenny Morris, Macmillan, 1993

[5] Disability, care and controlling services, Frances Hasler, In Disabling barriers – enabling environments, Edited by John Swain, Sally French, Colin Barnes and Carol Thomas, Sage, 2004

[6] Respite, Oxford Languages

[7] Care and support statutory guidance, Department of Health and Social Care, GOV.UK, Updated 22 July 2025

[8] Stop calling family carers a ‘hidden army’. We’re not invisible, just ignored, Mina Akhtar, The Guardian, 10 June 2020

[9] Labours of love, Madeleine Bunting, Granta, 2020

[10] No more throw-away people: the co-production imperative, Edgar Cahn, Essential Books, 2000

Leave a comment