I talk and write a lot about seeing people as human beings, about being human, and about how much of the way we currently work in the ‘human services’ is actually pretty inhumane. So, I thought it would be helpful to delve a little deeper, first to illustrate how our language dehumanises older and disabled people, and the absence of humanity in our systems, and then in a further blog post, to explore what it means to be human in our organisations and our practice.

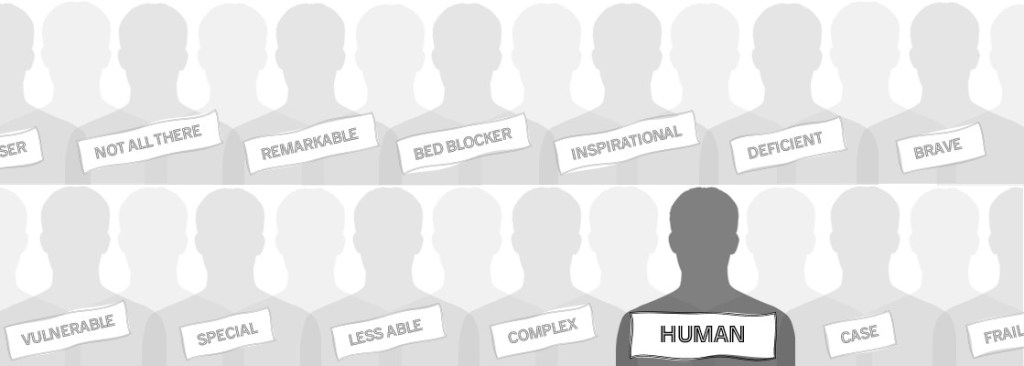

Human. A label we all share

As Elly Chapple rightly says, ‘human’ is “a label we all share”.[1] And yet many of the other labels we so liberally apply imply that older and disabled people are lesser human beings.

In a recent report, the Frameworks Institute observe that “when people believe that being human is tied to the existence of certain physical, mental, and affective abilities, anyone who lacks those abilities is seen as less human.”[2]

Not ‘us’.

Brene Brown writes that “dehumanizing always starts with language”[3], and Mark Neary observes that “language is the first step to turning people into non human objects.”[4] And there is a long history of such language in relation to older and disabled people.

Less human

The inference of people being ‘lesser’, ‘lacking’, ‘inferior’, ‘defective’ is pervasive and deep-rooted.

Terms like ‘idiot’, ‘cripple’, ‘invalid’ and ‘imbecile’ are centuries old. ‘Handicapped’ was first used in 1884. The Idiots Act became law in 1886, replaced in 1913 by The Mental Deficiency Act with its ‘definition of defectives’. Eugenicists in the late 19th and early 20th Century described disabled people as ‘feeble minded’ and ‘social rubbish.’ And the Nazi regime labelled disabled people as ‘useless eaters’ and ‘lives unworthy of life’.

Fast forward to today, and while our language may have changed, it still exposes the perception of older and disabled people as lesser humans.

Older people are labelled as ‘frail’, ‘deteriorating’, ‘declining’, ‘infirm’.

People living with dementia are described as ‘not all there’, ‘fading away’, ‘empty shells’.

Disabled people are viewed as ‘less-able’, ‘less healthy’, ‘physically challenged’, ‘suffering’, and as having ‘special needs’.

The language of ‘deficiency’ and ‘disorder’ is rife in relation to learning disability and neurodivergence, along with sweeping generalisations that autistic people ‘find communication and social interaction difficult’, ‘don’t feel emotions’, ‘lack empathy’.

And people with cause to draw on support are frequently described as ‘vulnerable’, implying weakness and helplessness.

All these words and phrases suggest that older and disabled people lack the characteristics and abilities of ‘normal’, ‘healthy’ human beings.

Of being human.

Our everyday language is also peppered with ableist phrases like ‘turning a blind eye’, ‘falling on deaf ears’, ‘having a senior moment’, ‘going insane’, ‘feeling paralysed’, ‘idiotic’, ‘dumb’, ‘senile’, ‘demented’ – associating ageing and disability with problematic, negative behaviour.

We can talk all we like about diversity and inclusion, but they are empty words when, rather than recognising that ageing and disability are part of human life and human diversity, our attitudes and our language and our actions reveal an underlying belief that some people are ‘normal’, and some people are ‘different’. And when we view inclusion as ‘fitting in’.

Superhuman

In contrast to the subhuman narrative, there is the portrayal of older and disabled people as superhuman.

“Japan’s ‘super-agers’ reveal secrets to extremely long life.” “102-year-old completes Great North Run.” “Disabled superhuman smashes fastest 10km scuba diving record.” “104 year old skydiver.” “80-year-old runner is just 5 secs slower than Usain Bolt”.

These stories tell of “remarkable”, “admirable” and “inspirational” people “overcoming disability” and “defying their age”. “Unsung heroes who battled disability to achieve their dreams.” “Olympians who overcame disabilities.” “An inspirational story of disability conquered.” “Elderly man defies age with downhill skiing.” “Meet two inspirational people that help others despite their own learning disabilities.”

This implies that impairments are barriers that disabled people must overcome themselves, and that they can be overcome with courage and determination. As well as helping to perpetuate the perception of disabled people as ‘shirkers’ and ‘skivers’ in contrast to these ‘strivers’, this narrative also removes all focus from addressing ableist attitudes, microaggressions, and disabling barriers in society.

Adjectives like ‘courageous’, ‘brave’ and ‘inspirational’ are also frequently applied to disabled people doing everyday things, whether by people in the street or by journalists in ‘motivational’ pieces. This led Stella Young to coin the phrase “inspiration porn” to highlight the objectification of disabled people for the benefit of non-disabled people.

In an article with the title ‘We’re not here for your inspiration’, she wrote that “using these images as feel-good tools, as “inspiration”, is based on an assumption that the people in them have terrible lives, and that it takes some extra kind of pluck or courage to live them.” She goes on to say, “my everyday life in which I do exactly the same things as everyone else should not inspire people, and yet I am constantly congratulated by strangers for simply existing.”[5] Her words are echoed in an article by Samantha Renke, who writes that “the assumption is made that disabled lives are lesser than others, therefore any hint of success or living a ‘normal’ existence must be exceptional.”[6]

The same, but different

‘The elderly.’ ‘The disabled.’ ‘The vulnerable.’ ‘The homeless.’ ‘The cared for.’ ‘Those with care and support needs.’ ‘Those with complex lives.’ ‘Those with LD.’ ‘Service users.’ Etc.

Oh, we do love to assign people to dehumanising boxes, defining people not as human beings, but by a single characteristic or circumstance.

Not only do these groupings imply that everyone in the categories is alike, but they also suggest that bit of distance.

Separate.

Other.

Not like us.

The same, but different.

Not human

Older people referred to as a ‘silver tsunami’ and a ‘demographic timebomb’. Disabled people described as ‘the wheelchair’. People in hospital labelled by their location (‘bed 6’, ‘chair 9’), or as being in the way.

“Bed-blockers help fuel the A&E crisis by taking up space from other patients”.

The implication that older and disabled people are objects, and that their presence is problematic or unwanted, is pervasive and reinforced by repeated references to people as ‘demand’ and as a ‘burden’.

Common terms like ‘feeding’, ‘toileting’, ‘grooming’ and ‘sitting services’ all bring to mind animals, not humans.

And we still keep talking about ‘users’ and ‘cases’ and ‘referrals’, not people.

Inhumane

The underlying belief, whether explicit in our thinking or buried in our consciousness, that older and disabled people are lesser humans, casts a long shadow over our practice.

Less human equates to less valued.

Less valuable.

As Mark Neary observes, “the minute someone is seen as non human, the door is opened to all sorts of unspeakable violence towards them”.[7]

This unspeakable violence includes violations of bodies and minds. Of identity and personhood. Of freedom and autonomy. Of hope and imagination.

When people are viewed as units of need, cases, objects, our organisations are designed to process and transact, not to relate. And as organisations grow, the potential for relationships diminishes. Our current ways of working are industrial sized and shaped, not human-sized and shaped – dehumanising the people working inside these institutions too.

The framing of older and disabled people as weak, vulnerable, not all there, less able, is used to justify paternalistic and restrictive practice that excludes people from decisions about their lives. Excludes people from a life.

Looking after.

Locking up.

Looking away.

Assigning people to boxes with their associated assumptions and judgements leads to one size-fits all responses and solutions.

Achieving our efficiencies as we erode unique identities.

And viewing people as ‘other’ stifles conversations and aspirations, with little consideration of the vital importance of love, joy, freedom, meaning and purpose.

Reflecting on spending time with people living in a care home, Madeleine Bunting writes that she was “overwhelmed by the sheer scale of human need bursting out of that neat building.”[8]

The visible ache of desire for connection.

A desperate need to feel human.

Individual

Perhaps in an attempt to redress this blanket categorisation and dehumanisation, we also refer to people as ‘individuals’. The Care Act statutory guidance emphasises that local authorities must have regard to “the importance of beginning with the assumption that the individual is best-placed to judge the individual’s wellbeing”.[9] ‘Personalised’ care and support is described in terms of “thinking of the person as an individual”. Working in a ‘person-centred’ way means “putting the individual at the centre of their care and support”. ‘Strengths-based’ approaches “support an individual’s independence.”

Ironically, often the way we use the term ‘individual’ makes it sound like another othering label, and indeed one dictionary definition of an ‘individual’ is “a person of a particular type, especially a strange one”.[10]

An individual is also defined as “a person considered separately rather than part of a group”.[11]

This is echoed in our practice focus on people as individual ‘cases’, rather than people being and becoming “who they are in relationship to others”.[12]

Too often we ignore the value and importance of connection and relationships. Of interdependency and reciprocity. Of belonging.

We also ascribe specific, desirable characteristics to ‘individuals’ – a generic mould we expect people to fit in to. We determine human value in terms of contribution and consumption. The Frameworks Institute paper describes two key assumptions of this mindset – that people are valuable to society “because of their economic productivity”, and “if they are self-sufficient”. The authors suggest that this “overemphasis on economic value makes it difficult for people to think about people’s social value more broadly, simply as humans”. [13] And Hilary Cottam suggests that “our systems – social and economic – are designed around who we imagine humans to be. Today that imagined human is the solitary, calculating and insatiable homo economicus… the individual who realises himself through a ruthless quest to maximise individual material gain”. [14]

These assumptions fuel our focus on ‘independence’ in terms of self-sufficiency, and the notion that people who require some additional support to live their lives are not only ‘lesser’, but also represent a drain on valuable reserves.

“Baked into the disability support system are eugenic principles that characterise disabled people as less than human and therefore unworthy of society’s scarce resources.”

Eddie Bartnik and Ralph Broad [15]

They also fuel our perception of people seeking and drawing on support as not trustworthy, leading to twice as much “‘checking’ (assessments, panels, scrutiny, supervisory oversight/justification, inspection etc)” as “‘doing’ (supporting, nurturing, connecting…even intervening), [16] and “the investment of up to 80% of welfare budgets on procedures for the policing/punishing of ‘deviants’ and so called ‘free-riders’”. [17]

Rehumanising

The dehumanisation of older and disabled people has perpetuated the systems and structures and institutions and roles we’ve created and has in turn distanced detached desensitised dehumanised us sufficiently to prevent us from questioning or challenging this narrative or this practice.

As Maya Angelou reflects, “we have to undo these lessons which have been learned by all of us. And not just taught to us – but we’ve learned them. And so it will be no small matter. But we can undo it. We can learn to see each other and see ourselves in each other and recognize that human beings are more alike than we are unalike.”[18]

We can have all the transformation leads and teams and plans and funds we like, but we’re never going to achieve real, meaningful, lasting change until we learn to see each other and see ourselves in each other and recognise that human beings are more alike than we are unalike.

And, as Brene Brown observes, “because so many time-worn systems of power have placed certain people outside the realm of what we see as human, much of our work now is more a matter of “rehumanizing.” That starts in the same place dehumanizing starts—with words and images.”[19]

Us, not them and us.

Human.

A label we all share.

References

[1] Elly Chapple Founder #FlipTheNarrative, Elly Chappell, Twitter, 2024

[2] Communicating about Disability in Australia, Patrick O’Shea, et al. Frameworks Institute. 2023

[3] Dehumanizing always starts with language, Brene Brown, Brene Brown, 17 May 2017

[4] The words on the tin, Mark Neary, Love, Belief and Balls, 2 December 2018

[5] We’re not here for your inspiration, Stella Young, ABC, 2 July 2012.

[6] I don’t want to be your inspiration porn, Samantha Renke, Metro, 2 February 2021.

[7] The words on the tin, Mark Neary, Love, Belief and Balls, 2 December 2018

[8] Labours of love, Madeleine Bunting, Granta, 2020

[9] Care and support statutory guidance. Department of Health and Social Care, GOV.UK. Updated 19 January 2023.

[10] Individual, Oxford Learner’s Dictionaries

[11] Individual, Oxford Learner’s Dictionaries

[12] A radical new vision for social care: How to reimagine and redesign support systems for this century, Hilary Cottam, The Health Foundation, November 2021

[13] Communicating about Disability in Australia, Patrick O’Shea, et al. Frameworks Institute. 2023

[14] A radical new vision for social care: How to reimagine and redesign support systems for this century, Hilary Cottam, The Health Foundation, November 2021

[15] Power and connections, Eddie Bartnik and Ralph Broad, Centre for Welfare Reform, 2021

[16] Eligibility criteria – what if we just turned them off?, Mark Adam Smith, Changing Futures Northumbria, 10 August 2022

[17] A radical new vision for social care: How to reimagine and redesign support systems for this century, Hilary Cottam, The Health Foundation, November 2021

[18] An Interview With Maya Angelou, Marianne Schnall, Marianne, Psychology Today. [17 February 2009.

[19] Dehumanizing always starts with language, Brene Brown, Brene Brown, 17 May 2017

Leave a reply to Bryony Shannon Cancel reply