While the word ‘bed’ might not have the same depth of meaning as ‘home’, if you think about your own bed, it may well evoke similar associations and emotions.

Familiarity. Safety. Privacy. Comfort. Warmth. Family. Love. Belonging.

Hilde Lindeman suggests that “it’s not only other people who hold us in our identities. Familiar places and things, beloved objects, pets, cherished rituals, one’s own bed or favorite shirt, can and do help us to maintain our sense of self. And it is no accident that much of this kind of holding goes on in the place where our families are: at home.” [1] [emphasis added]

Often our beds are the place we’re glad to return to after time away – ‘it’s so good to be back in my own bed’. A place to retreat, relax, rest and recharge. Sometimes our beds are places we long to leave. And at times our beds may be places we’re scared to climb in to – or actively avoid.

No doubt we’ve all experienced the desire to hide under the duvet. Sobbed into our pillows. Felt at our most lonely, and/or our most loved, in our own beds. They can be the locus of delicious pleasure, and of devastating pain. Hope and heartbreak. Dreams, and nightmares too.

So many lives begin, play out, and end in a bed.

Gloriously ordinary lives.

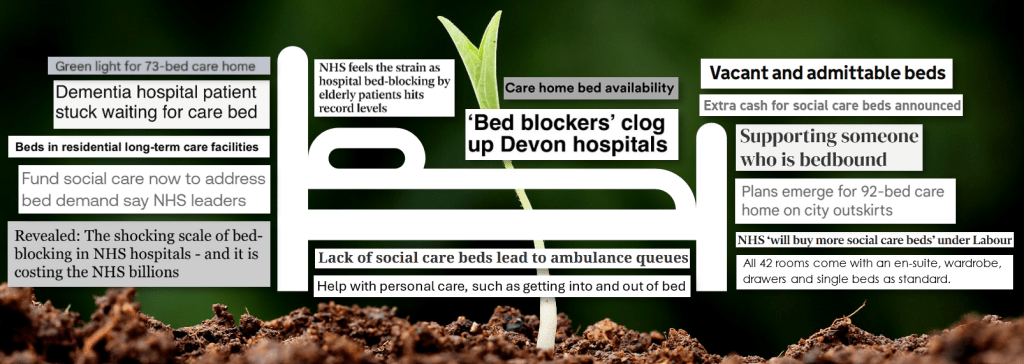

But the way we talk about beds in social care represents thinking – and exposes a reality – that is anything but gloriously ordinary.

How often we refer to social care beds assessment beds community beds care home beds respite beds nursing beds hospital beds EMI beds NHS beds inpatient beds acute beds residential care beds admittable beds rehabilitation beds step down beds virtual beds emergency beds blocked beds vacant beds.

How rarely we mention ‘own beds’.

Social care beds

“Badly needed hospital beds are being taken up by patients who should be treated in care homes — but there are not enough care beds nor facilities for the sick and elderly.”

“Buying up spare social care beds will create much needed capacity.”

The first ‘point of interest’ in the Department of Health and Social Care’s monthly statistics about adult social care in England is the “percentage of occupied, vacant and admittable, and vacant and non-admittable care home beds.” [2]

The second key finding in the latest Care Quality Commission report on the state of health care and adult social care in England relates to “waits for care home beds.” [3]

Reflections on, and communications about, social care ‘capacity’ and social care more generally so often include references to beds. Social care beds. Care beds. Care home beds.

This is frustrating in so many ways.

The repeated references to beds link social care with illness. With “patients who should be treated in care homes”. Helpless, passive folk who must be looked after and cared for. There’s an inevitable association with decline and the end of life – far removed from any sense of support for people to flourish and thrive, at whatever age or stage.

Framing social care in relation to beds cements an association with institutions. Places to put people. Care as a destination.

‘Bedded care facilities.’ ‘Bedded settings.’ ‘Intermediate care bedded units.’ ‘Bed based services.’

It’s a narrow, sterile perspective – and existence. “The average number of beds is 29.5 per care home but the range is from a single bed to 215 beds.” [4] 215 beds! We’re still warehousing older and disabled people. And as Frances Ryan writes, “the term “warehoused” conjures up the chilling reality: human beings stored under one roof without autonomy, control or dignity.” [5]

I was interested to see The Kings Fund explicitly note that “we use the term ‘places’ in preference to ‘beds’” in the section on ‘care home places’ in their ‘Social care 360: providers’ analysis. [6] ‘Places’ may offer a slightly broader lens, but it still implies placement and transience. It’s devoid of any notion of humanity and belonging.

So much for living in the place we call home.

This framing of social care ‘capacity’ also perpetuates the narrative of scarcity, overlooking the value and potential of alternative, ‘ordinary’ resources and support within families and communities – as highlighted so brilliantly by Community Catalysts in their Mavis and Meena video. As Angela Catley writes, this means we’re squeezing the abundance out of view, and narrowing the choices and options open to people – for example by “telling people they need to move to a care home when we actually mean… we don’t have the time, connections or resources to work with you and your family to knit together the creative tapestry of support you will need if you are to stay at home.” [7]

Freeing up hospital beds and reducing bed days lost

“There is ‘barely a spare bed’ left in NHS hospitals due to a lack of capacity in social care.”

“One in seven beds in NHS hospitals are taken up by patients who are well enough to leave but are waiting for social care.”

“Care worker shortage blocking hospital beds.”

When social care gets a mention in the press, it’s usually in relation to stories about hospital beds – and generally blamed for “pressure on the NHS”. As such, ‘beds’ feature heavily in the narrative of social care reform. The previous Conservative government linked extra funding for social care to prioritising “those approaches that are most effective in freeing up the maximum number of hospital beds and reducing bed days lost.” [8] Ahead of last summer’s election, Labour announced that the NHS would “be encouraged to buy up social care beds in a bid to get medically-fit patients out of hospitals faster”. [9] And the government’s recent press release on ‘transforming’ social care refers to “helping to keep older people out of hospital” and “taking pressure off the NHS”. [10]

It’s a narrative of reform that’s focused primarily on freeing up hospital beds, not on equality, rights, and building better lives.

Bed blockers

While our ‘own bed’ may help us maintain our sense of self, the way we refer to people in relation to beds does just the opposite.

‘Bed blockers.’ ‘Bedbound.’ ‘Bedridden.’ ‘Bed seven.’

These deficit-based, medical model terms present people as problems. In the way. Invalids. Invalid. Invisible.

Never mind gloriously ordinary lives – there’s no evidence of life in this narrative.

And there’s plenty of evidence to show how our practice is shaped by this lack of acknowledgement that we all want, and need, a full and equal life.

Getting in and out of bed

‘Help getting in and out of bed’ is invariably included in descriptions of the purpose of adult social care, alongside assistance with other ‘activities of daily living’ like eating, washing and getting dressed. In the depths of serviceland, a long, long way away from gloriously ordinary, getting in or out of bed becomes “a bed transfer”. “Supporting patient transfers from bed to chair”. “Support to mobilise patients out of their bed.”

We focus our attention on whether people require assistance to get in and out of bed and forget to consider whether people have a reason to get up.

Bedtimes

“Where we live, with whom, what we eat, whether we like to sleep in or go to bed late at night, be inside or outdoors, have a tablecloth and candles on the table, have pets or listen to music. Such actions and decisions constitute who we are.”

Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities [11]

The pleasure of a ‘nice early night’. The thrill of staying up until dawn. Whether we’re ‘early birds’ or ‘night owls’, we can generally choose the time we get up and go to bed, and “such actions and decisions constitute who we are.”

But we know that far too many people who draw on social care support don’t have that choice. The time people get up is scheduled and set. “Evenings [are] cut short because of inflexible rotas for support staff, blanket curfews or residential homes locking their doors at 10pm.” [12]

“Told them I don’t like going to bed at 7 o’clock at night. Carers come at 8.30am – 9am in the morning so I asked if they could come later, they said ‘No’ because everyone has a set time and it can’t be changed.”

Care Quality Commission [13]

Everyone has a set time and it can’t be changed.

Single beds

When you picture all these ‘social care beds’, what size are they?

Open Future Learning founder Ben Drew told a story on LinkedIn recently about supporting Clive, “a 74 year old man who had spent all of his life in care” to move into his own home when “the large group home that Clive lived in was closing.” Due to the tight timescales of the move, while Clive went shopping with his support worker, Ben went off to IKEA to buy him a bed. He explains that he assembled the bed and was excited to show it to Clive…

“Clive stood in the doorway, silent, his gaze fixed on the modest frame. I watched his face as emotions rippled across it. This wasn’t just a bed. For Clive, it symbolized something monumental: the end of a lifetime in systems and services and the start of something new.

Finally, he turned to me. His voice, though quiet, carried a depth I’ll never forget: “Where’s my girlfriend going to sleep?”

His question hit me like a bolt of lightning. I didn’t know Clive and my assumptions were laid bare. His life of systems of services was far from over.

To me Clive was a 74 year old man with an intellectual disability, single, sexless. I’d spent years advocating for people to have full lives, including relationships, and yet I had unconsciously excluded Clive from that vision.”

Ben Drew [14]

And in an article about the findings from a social media poll asking why so few people with learning disabilities sleep with a partner, Dr Claire Bates notes that often people only had a single bed, suggesting “single beds = single lives.” She writes, “perhaps the saddest option could be that people did not even expect this. Going to sleep snuggled up next to your nearest and dearest is not even considered as ‘something for people like me.’” [15]

Flower beds

Away from the assumptions and expectations of serviceland, there’s another type of bed, full of rich, fertile soil. A place for deep roots. For seeds full of possibility and potential. For plants to grow tall and for vibrant flowers.

I’ve suggested before that we need to leave behind the divisive language of the battlefield (frontline, duty, officer, hero…) and the mechanistic language of the sorting office (efficiency, screening, triage, outputs…) and be influenced instead by the bountiful, beautiful, and optimistic language of the natural world. [16]

So how about we start associating social care with flower beds instead of hospital beds? Because we all need the space and the opportunity and the love and the support to flourish and to bloom.

References

[1] Holding one another (well, wrongly, clumsily) in a time of dementia, Hilde Lindemann, Metaphilosophy, Volume 40, Issue 3-4, July 2009

[2] Adult social care in England, monthly statistics: October 2024, Department of Health and Social Care, GOV.UK, Updated 6 February 2025

[3] The state of health care and adult social care in England 2023/24, Care Quality Commission, 25 October 2024

[4] Care homes as a model for housing with care and support, Social Care Institute for Excellence

[5] Think of this: a plan to ‘warehouse’ disabled people. What kind of nation is Britain becoming?, Frances Ryan, The Guardian, 25 January 2024

[6] Social Care 360: Providers, The King’s Fund, 13 March 2024

[7] Mavis and Meena – social care abundance or deficit? Angela Catley, Community Catalysts, 30 May 2023

[8] Our support for adult social care this winter, Policy paper, Department of Health and Social Care, GOV.UK, 11 January 2023

[9] NHS ‘will buy more social care beds’ under Labour, Ella Pickover, The Independent, 18 June 2024

[10] New reforms and independent commission to transform social care, Department of Health and Social Care, GOV.UK, 3 January 2025

[11] General comment on article 19: Living independently and being included in the community, Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, Eighteenth session, 29 August 2017

[12] Our Fight – Campaigning for great lives, Stay Up Late

[13] Profad Care Agency Limited Inspection report, Care Quality Commission, 11 July 2022

[14] At thirty, I have been supporting people…, Ben Drew, LinkedIn, January 2025

[15] We have opened the Valentine’s can of worms – have you?, Dr Claire Bates, Learning Disability Today, 9 February 2018

[16] Rewilding social care, Bryony Shannon, Rewriting social care, 8 April 2023

Leave a reply to Beds – Making Home Home Cancel reply